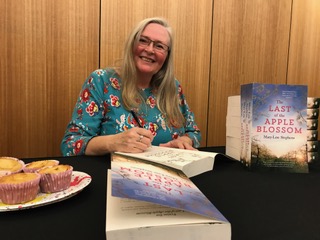

Mary-Lou Stephens (Class of 1978) from traveller to writer

Posted on July 15, 2024

Mary-Lou Stephens (1978) didn’t know what she wanted to do when she completed Year 12 at Friends’. Her parents’ advice to “get some life experience” set her on paths that have ultimately led to her travelling continually rather than residing in one place, and becoming an author, most recently of the Hobart-set historical novel The Chocolate Factory.

What sparked the idea for your latest novel?

I wanted to write a book about Quakers. As I’ve grown older, I’ve become much more in tune with their values. There’s also the delightful fact that Quaker families started all the big chocolate factories in the UK – Cadbury’s, Rowntree’s and Fry’s. Town water would make people sick so everyone was drinking beer, causing social problems. So in the 18th and 19th centuries the Quakers presented hot chocolate to the public as an alternative to alcohol.

And each chocolate factory wanted the others’ secrets.

When George Cadbury Jr created Dairy Milk in 1905, it quickly became the most popular chocolate ever. Everyone was trying to steal the recipe. Companies would employ spies to go into their opponents’ factories, and then the factories would employ chocolate detectives to try and sniff out the spies. Roald Dahl, who went to a boarding school near Cadbury’s in England where he and the other boys were taste-testers, was fascinated by all the industrial espionage. It’s why in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Willy Wonka shuts the gates and stops employing people.

Which arrived first in Hobart – chocolate manufacturing or the Quakers?

There was already a well-established meeting house in Hobart by the time Cadbury’s came in 1921. Australia was a huge market for the company but it was stymied by tariffs and then World War I, when chocolate imports were banned. They built the factory in Claremont for the cool climate and fresh water but the thing that clinched the deal was Tasmania’s cheap hydroelectricity. Quakers were extremely good at business. Because they wouldn’t swear the Oath of Allegiance to the Crown, they weren’t allowed to study at the universities. So instead of becoming doctors and lawyers, they entered business.

Was there resentment towards a British company coming onto the island?

Not from Hobartians but certainly confectioners on the mainland – MacRobertson’s, Hoadley’s and Allen’s – wanted to hold on to their market share. MacRobertson’s controlled most of Australia’s glucose supply and tried to restrict it but Cadbury’s found a small, willing supplier before glucose became freely available.

In your portrayal, Cadbury’s factories and their surrounds seem beautiful. Were they intentionally creating beauty for workers?

There’s the famous quote from George Cadbury: “No man ought to be condemned to live in a place where a rose cannot grow.” The Quakers were very much into health: lots of light and ventilation in their factories and an emphasis on exercise and eating well. In the late 1800s, the Cadbury family created the beautiful village of Bournville for their factory workers, bringing them out of Birmingham’s slums. Cadbury’s hoped to do the same at Claremont by establishing sports grounds and including gardens with each cottage. The big factory windows did backfire a little; in the Pascal’s section where they were boiling lots of sugar syrup, the workers complained it was too hot.

How did the Quaker view of equality of genders play out in the Claremont factory?

In confectionery, women were at least 50 per cent of the workforce. There were still constraints of the times – women were paid well but mostly not the same as men – but they were highly respected and able to rise through the ranks.

Did Quaker thinking appeal while you were at Friends’?

I liked going to the meeting house and sitting in silence but because my parents were Pentecostals there wasn’t room for the quiet, understated philosophy of Quakerism. When I finished year 12, I didn’t know what I wanted to do, and my parents were keen for me to get some life experience. My great aunt, Margaret Watts (née Thorp) had died – she was a Quaker activist known as The Peace Angel during the First World War – so I was able to live in her apartment close to Kings Cross. I got a lot more life experience than I expected! One night I went to see The Stranglers play and I heard this sound and just fell in love with it. It was the sound of the bass guitar. I’d finally found what I wanted to do. I wanted to be a bass guitarist.

Did you study?

I bought a bass guitar, moved back to Hobart and had a few lessons, but most of the time I just made it up. I played with Impractical Acts and Shirt of Decency before playing in Melbourne bands while I studied acting at the Victorian College of the Arts. Then I played in Mary-Lou and the Broken Hearted in Hobart and moved to Sydney. When my last band, Chain of Hearts, broke up in 1996, I was 35 and heartbroken. My friend [then ABC broadcaster] Chris Wisbey said, “You want to be in radio,” and it was a lightbulb moment. Every door opened. I trained at the Australian Film, Television and Radio School and eventually landed my dream job as a music director and announcer at the ABC on Queensland’s Sunshine Coast.

When did you start writing?

I’d never thought I’d write novels – I wanted to be a famous singer-songwriter – but I was asked to write a weekly column for the local newspaper. I started taking courses, wrote some short stories and saved to take six months’ leave without pay. I worked with a mentor and a plan to find out whether I could complete a novel in six months then want to do it again. The answer was yes. My memoir Sex, Drugs and Meditation came out in 2013 but it took three practice novels – they will never be published – before The Last of the Apple Blossom [set in Huon Valley] came out in 2021. [Mary-Lou’s next historical novel The Jam Maker, set in Hobart’s jam factories, will come out in February, 2025.]

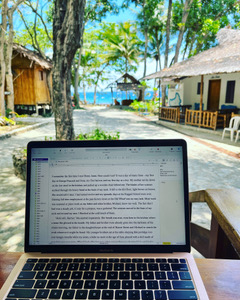

You tell Tasmanian stories but live all over the world. Where are you now?

I’m in Uruguay, right on the Atlantic Ocean. When I left the ABC in 2016, all I wanted to do was travel and write. My husband Ken discovered “slow” travel, which is an affordable way of seeing the world. I’ve been an actor, a musician and a writer, so I know how to live frugally. With slow travel you stay in one place for as long as a tourist visa allows, so you save on accommodation and travel costs. It also means you get to know the culture better and, hopefully, a little of the language. We spent last year in Malaysian Borneo, Vietnam, Thailand, Cambodia and on a small island in the Philippines. Next we’ll travel through South America and Central America to Mexico. Well, that’s the plan. With slow travel, plans can change.