Professor Brett McDermott (Class of 1978) Awarded by Order of Australia

Posted on November 18, 2024

Taking Care of the Children

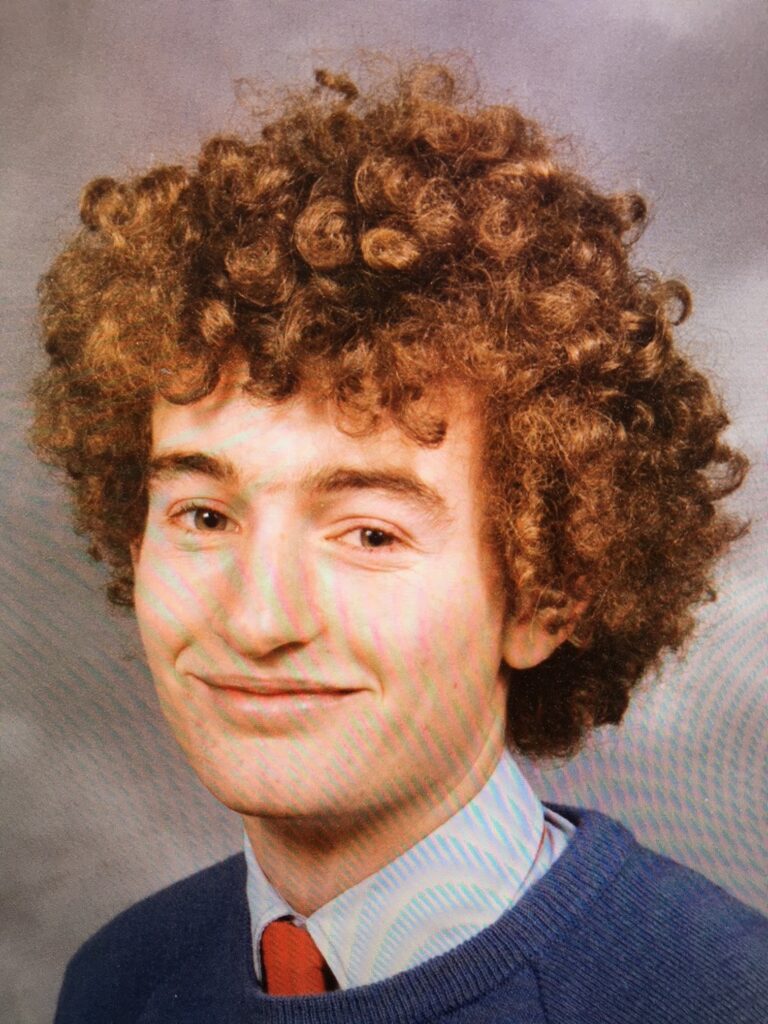

This year, Professor Brett McDermott (Class of 1978) was made a Member of the Order of Australia for services to medicine in the field of child and adolescent psychiatry. Here he describes his path from a “boofhead” at Friends’ to Director of the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service Tasmania.

What drew you to psychiatry?

I went straight from Friends’ to uni, so I was a doctor at 22. There was a pivotal moment when I worked for someone who said, “How’s the appendix in bed three?” And I said, “That’s Mrs Jones. She’s 43 and struggling because she doesn’t have a lot of money or support. We took out her appendix, but she wants to get out of hospital sooner than she should to get back to her three children.” They weren’t interested in any of that. From early on I was interested in the person and in an illness being centred in a human being. I also wanted to give testimony to the person’s journey and struggle.

Why your particular interest in child and youth psychiatry?

I’ve always been very interested in the child-adolescent journey, and I think this interest comes across in therapy. I can be a bit untraditional – I do art and make jokes. Some people misinterpret that, but children don’t. They understand I take things very seriously.

I also think the work is optimistic. Children and adolescents have a whole life before them. If you can deviate their trajectory up a little bit, that little deviation over 10 or 15 years is a huge difference. They often haven’t met adults who’ve had complete and total regard for them. I’ve met children who have never received a compliment. If I said, “I’m really proud of that effort, that was fantastic,” they’d look at you and you could see them thinking, “What does that mean?”

That’s really sad.

Oh, yes. I have 35 years of minor cumulative moral injury from the ways some families treat children.

What was your path after Friends’?

Uni was free then – there was no HECs – but at the same time I had no kind of living money, so I joined a rifle company in the Army Reserve where the pay was tax-free. During the last years of studying medicine at Utas you move around the state, so I took up a bonded position with the Royal Australian Navy. For three years I wandered around the South Pacific and Asia and that’s when I got interested in mental health and treatment of drug and alcohol challenges.

Did it suit you, the Navy life?

Yes and no. I was sporty; I’d done a couple of Sydney to Hobart Yacht Races. But in my first year of marriage [Henry married Dr Catherine Brown in 1988], I was away at sea for 40 weeks. I remember once my wife and I were going to meet at Expo 88 in Brisbane, and I woke up that morning and Australia was on the wrong side of the ship; the skipper said there was a military coup in Vanuatu, and we were going.

What did you do after the Navy?

Cath and I started off as doctors in the then Sydney to Darwin overland car race, the Wynn’s Safari. From there we travelled to Indonesia and Singapore and lived on a beach in Thailand for a dollar a night; if someone made a banana smoothie the lights would go out because there was only enough power for one or the other. We flew over wars and hotspots. We couldn’t get into Burma and Myanmar, so we flew to Nepal, where we saw elephants and snow, and then Kashmir and Turkey. It was an amazing 10 months, but we did all our money and needed to get jobs quickly.

What did you do?

Cath got a job in London straight away because she was happy to do neonatal intensive care, which is hard. It was easy for me too because I wanted to do psychiatry; it wasn’t popular or well-funded then, even in the so-called developed world. Psychiatry takes a doctor away from their medical training, where you spend years learning how to read X-rays and blood tests that are little used in psychiatry. You also have to embrace complexity; there’s nothing more complex than a mental health presentation and there’s no scaffolding of biometric testing. And you need to be really good with people and happy sitting with them at their most distressed.

We came back to Sydney in 1991 after our first child appeared. [They now have three children, living in Sydney, New York and London.] I finished my specialist training as a psychiatrist and worked in Newcastle and Perth, where I became a professor at the University of Western Australia, and then in Queensland running a CAMHS [Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service]. During that time, I was on the board of Beyond Blue.

You returned to Tasmania to be close to your parents during the pandemic. Why did you stay?

I wrote a review of the local child and adolescent mental health services that said it really needed help. The government came up with $42 million to fund the review but couldn’t find the appropriate person to run it. Cath and I had been thinking about returning to Tasmania. For three years now, I’ve been the director of Tasmanian Child and Youth Mental Health and engaged in actualising the CAMHS reform plan I wrote.

Where will the $42 million go?

Tassie was underfunded in terms of child and adolescent mental health. If you were a child from an intact family and had a moderate anxiety condition and could get to the clinic, you got a really good service. But if you were a kid who couldn’t get to a clinic – because you had severe and complex mental illness, lived in and out of care, were episodically homeless or had drug-induced psychosis – you couldn’t get the service despite clearly having the greatest need. There was no child and youth inpatient unit for more intensive work, no day program or after-hours hospital help or service outside of clinics. This was not the fault of the staff; the service was set up this way because of lack of funding.

We’re engaged in a rebuild. We’ve doubled the staff of the service and hope to double it again. Probably half of our teams will have an out-of-home brief – we’ll go to kids in their accommodation. We’ve started an after-hours hospital team, a youth service and a team using a model called Multisystemic Therapy, which has good evidence of helping kids stay out of youth detention by empowering family to help them. We’ve started a Tasmanian eating disorders service, a youth hospital-in-the-home in the north west, and a research centre, the Tasmanian Centre for Mental Health Service Innovation. The clinics will get smaller in size, but there’ll be more of them in more locations around the state.

Are there mental health issues that are particularly pronounced in Tasmania’s young?

There are contemporary themes for youth and, because of the internet, these are not too different in Estonia or Indonesia. The themes are, and not in this order…

Climate anxiety: people are justifiably concerned about climate change, particularly people who are indigenous. I know some young people who are thinking about whether they should have children.

Vicarious trauma is another issue. When I was a kid, you left the world’s troubles after the 7pm news or you didn’t hear about them. Now you can be engaged in Ukraine or Gaza 24 hours a day if you want. There are people at risk – those who can’t disengage with being bullied or their body image – but research evidence suggests social media is not always a problem. For some young people, social media improves their mental health; others are very savvy about their online profile.

And of course there’s injustice: perceived cost of living injustice, perceived HECS injustice, feelings about wealth locked into generations and the obvious and ongoing injustice about indigenous voice and indigenous identity and rights. A couple of colleagues wrote a paper I wish I’d written [More Than Skin Deep: Stress Neurobiology and Mental Health Consequences of Racial Discrimination, 2015] that found perceived injustice not only caused chronic low-grade depression and feelings of worthlessness and low self-esteem, but it also affects your physical body. It causes dysregulation of your stress hormone system and your immune system. Allostatic load is a new concept related to body wear and tear. Injustice is a cause of increased body wear and tear.

What was your own experience as a child?

I was an Army/Navy brat. Because both my parents were in the military, I grew up on “marriage patches”, where military families would live together side by side in houses in the suburbs. I was born on the Navy base on Manus Island and went to more than 10 schools before I came to Friends’ to get the last five years of my schooling in one place. This was a revelation. The teaching was very individualised. In Year 11, the teachers made this plan to get my marks up in maths, because they knew how much I wanted to get into medicine. I think seven of us got into medicine that year. Everyone used to call me Springer because I had this ridiculous, boofy, ’70s hair. I was a natural boofhead! But no one cared at Friends’. It was an incredibly warm and accepting environment.